In 5 articles, you’ll get a deep dive of Kinsale Capital Group (~100 pages).

It will be structured in five Parts plus one additional fundamental piece:

Part 1 (today): Insurance 101 and E&S playground

Part 2: Regulation: Why E&S looks the way it does

Part 3: Kinsale’s Business Model

Part 4: The Kinsale machines: Understanding the Financials

Part 5: Compounder?

“The Fundamentals”: Reinsurance 101

All parts are now available in one PDF. You can download it below.

👔 Company Name: Kinsale Capital Group (“Kinsale”)

🔎 ISIN: US49714P1084

🔧 Business model: Specialty insurer (Excess & Surplus lines)

🌍 Geographic exposure: United States

📈 Stock Price: $393

💰 Market Capitalization: $9.1 billion

👨💼 Number of CEOs since foundation: 1

👨👩👦 Founder-/Owner-operator: Yes

📅 CEO tenure: Since 2009

🥇 Insider ownership: 5.5% of shares

📊 10Y EPS CAGR: ~41%

🔁 Reinvestment profile: High (float-funded growth)

💸 Capital intensity: Capital-light

🏰 Moat: Specialization, Focus, Technology & Cost Advantage

🧨 Main risks: Cyclicality, Broker concentration, Investment risk, Reserve adequacy, Regulatory risk

🌳 Slow Compounding fit: Yes – high-quality underwriting, long growth runway

Business Model in a Nutshell: Kinsale is a U.S. specialty insurer focused 100% on commercial Excess & Surplus Lines, insuring hard-to-place risks that standard carriers decline. The company runs a high-volume, low-hit-rate underwriting model, supported by a proprietary tech platform that lets underwriters quote small and mid-sized accounts quickly and selectively. Economics are driven by disciplined underwriting (combined ratio mid-70s) and float-funded investment income.

1. Why this boring niche is worth your time

Kinsale Capital Group is the only publicly traded pure-play Excess & Surplus Lines (E&S) insurer in the United States. On the surface, that sounds like a dusty corner of the market: a small specialty carrier, writing obscure commercial policies for risks that most investors have never heard of. But once you understand the niche Kinsale plays in, the structure of the U.S. insurance market around it and the way the company has built its operating model, it becomes a very different story. This is not a typical insurance compounder built on scale and marketing. It is a focused, data-driven business operating in a part of the market that is both structurally attractive and still widely misunderstood.

At its core, Kinsale does something very simple: it underwrites insurance policies for risks that the standard, heavily regulated market does not want. Whenever a retail broker has tried the usual admitted carriers and received only declines, the next step is often to approach the E&S market via a wholesale broker. Kinsale has positioned itself exactly at this choke point. It wants to see as many of these difficult risks as possible, and then to write only the ones where the odds are clearly in its favour.

The rest of this first part sets the stage. We start with the basic mechanics of how a property and casualty (P&C) insurer makes money, look at the big buckets of the U.S. insurance market and then zoom in on the E&S segment. From there, we map out what kinds of risks end up in E&S, who the main players are and how Kinsale fits into this ecosystem. The goal is simple: by the end of this part, you should have a clear mental model of the playground in which Kinsale operates.

1. How an insurer earns money

1.1. The basic contract

Insurance starts with a contract. The insurer promises to compensate the policyholder or a beneficiary if a defined event occurs – a building burns down, a customer is injured on the premises, a professional makes a costly error, for instance. In return, the policyholder pays a premium.

If no insured event occurs during the coverage period, the policyholder has paid for peace of mind, and the insurer keeps the premium.

If a covered loss does occur, the insurer pays according to the terms of the policy.

From the policyholder’s perspective, the value is obvious: an uncertain, potentially ruinous loss is turned into a known, manageable expense.

From the insurer’s perspective, the key is aggregation. By pooling a large number of independent risks, it can estimate the average loss for a portfolio much more reliably than for any individual policy. That is the economic basis of insurance: diversify many small independent risks, price them correctly on average and add a margin for expenses and profit.

At heart, an insurer is a professional risk manager. It uses data and experience to estimate how likely insured events are to occur and how costly they will be when they do. These estimates drive the premium: the higher the expected loss, the higher the price. Two dimensions matter most for pricing:

First, how likely is it that a claim will occur at all?

Second, if a claim occurs, how large is it likely to be?

In practice, insurers also adjust for the risk profile of a particular policyholder. A younger driver will pay more for auto coverage than a careful driver with a clean record. These differences are reflected in the premium.

If premiums are set too high, policyholders will eventually migrate to cheaper competitors. If they are set too low, claims will eat through the premium income and the insurer will lose money over time.

1.2. Losses, expenses and the combined ratio

On the income statement, the economics of a P&C insurer are usually summarised in the combined ratio.

The loss ratio measures incurred losses and loss adjustment expenses relative to earned premiums. The expense ratio measures acquisition, underwriting and other operating expenses relative to earned premiums. Together, they form the combined ratio.

A combined ratio below 100% means the insurer is making an underwriting profit before investment income; a ratio above 100% means underwriting is losing money and needs to be subsidised by investment returns.

Over long periods, the U.S. P&C industry as a whole tends to hover around a combined ratio of roughly 100%. Some years are better, some worse, but the industry is not built to deliver large underwriting margins. The product is often a commodity, and competition tends to push prices down to a level where the average carrier just breaks even on underwriting. That is why Warren Buffett so often emphasised that the value of an insurer lies in two things: its discipline in underwriting and its skill in investing the float.

This backdrop makes Kinsale’s track record stand out. Over the past years, the company has consistently operated with a combined ratio in the mid-70s and an expense ratio in the low 20s. In a sector where most peers fight for low single-digit underwriting margins at best, a 25-point gap in the combined ratio is not a small efficiency tweak – it is a structural advantage that compounds over time.

We will go into the details in Part 4 of this Deep Dive series. We will break down how Kinsale achieves these strong results.

2. The big buckets of the U.S. insurance market

2.1. P&C, life, health – and reinsurance on top

The American insurance market is usually divided into three main primary segments:

Property and Casualty (P&C): P&C – sometimes called general insurance – covers both assets and liability. Property insurance protects tangible items such as vehicles, buildings or household contents – for example auto, homeowners’ or renters’ insurance. Liability insurance protects against third-party claims, covering damage to others’ property or injuries to other people for which the policyholder is legally responsible, such as general, professional or product liability.

Life and Annuity: Life and annuity business focuses on mortality and longevity risks, often with an investment component.

Health: Health insurance covers medical expenses and disability-related risks.

On top of these primary segments sits reinsurance. Reinsurers do not deal with end customers. Instead, they provide capacity and risk sharing for insurers themselves. Primary insurers can cede part of their risks to reinsurers to smooth their results, protect their balance sheets or reduce the amount of capital they need to hold. Reinsurance is important for Kinsale, but we will dedicate a full part of this deep dive to that topic (Part 2 of this Deep Dive series).

2.2. Personal vs. commercial, standard vs. specialty

Within P&C, it is useful to distinguish between personal and commercial lines. Personal lines protect individuals and households – think private motor, homeowners or renters insurance. Commercial lines cover businesses and organizations, from small local shops to large multinationals. These can range from simple property policies for a small warehouse to complex liability programmes for industrial plants or professional service firms.

Most of the premium volume in the U.S. still comes from standardized personal and commercial products offered by admitted carriers. These are large, regulated insurers whose rates and policy forms must usually be filed with and approved by state regulators. Admitted carriers participate in state guaranty funds and operate under extensive consumer-protection rules. Their business is designed around high volume, relatively homogeneous risk pools and a high degree of automation.

Kinsale plays in a different corner of the market. It operates exclusively in commercial lines and almost entirely in specialty products that are written on a non-admitted, surplus lines basis. The risks it insures are often too complex, too unusual or too small for the standard admitted market to handle efficiently. Understanding why this separate channel exists is the key to understanding Kinsale’s opportunity set.

3. What exactly is Excess & Surplus Lines?

3.1. The safety valve of the U.S. system

E&S stands for Excess & Surplus Lines. Other common labels are “non-admitted”, “non-standard”, “unlicensed” or simply “surplus lines”, in contrast to the admitted or authorized market, where products are more tightly regulated and standardized.

E&S is the safety valve of the U.S. insurance system. It deals with risks that the admitted market does not want or cannot easily accommodate.

Admitted insurance carriers focus on high-volume products with relatively stable and well-understood loss patterns. Their rates and policy forms are usually subject to prior approval or at least filing requirements. That makes the system predictable and consumer-friendly, but also slow and inflexible.

When a new type of risk emerges, or when a risk is highly unusual or “hard-to-place”, admitted carriers often cannot or will not provide coverage. Regulators therefore allow a separate channel – the surplus lines market – where pricing and policy design are much more flexible, but where policyholders do not enjoy the same level of regulatory protection.

Standardized insurance is provided by admitted carriers that are licensed in a given state. They must comply with capital requirements, investment rules and market conduct standards and typically participate in guaranty funds that protect policyholders if an insurer fails. Think of auto or homeowner insurance, which covers common risks that are straightforward to assess and insure.

E&S insurers, by contrast, are not “admitted” in the states where they write surplus lines business. They operate under different rules: they have more “freedom of rate and form”, meaning they can price and structure individual risks independently without requiring rate adjustments to be approved by regulatory authorities.

E&S insurers specialize in developing new coverages and tailoring policies to unique risks. Once coverage has matured, enough data has been accumulated and the risk has become more standardized, it may eventually migrate into the admitted market. That transition can take years or even decades. Until then, E&S carriers are the laboratory in which new types of coverage are tested.

It is important to note that risks written in the E&S market are not necessarily riskier than those in the standard market. The real challenge is that they are harder to assess – they are more complex, less standardized and therefore require more specialized underwriting approaches.

3.2. A brief historical detour: why the E&S channel emerged

The insurance landscape as we know it today has evolved over centuries. Early insurance companies started as small, local entities focused on a narrow set of risks – often fire risk in a particular city or marine cargo on specific trade routes. The result: Geographic customer concentration risk for insurers.

In 1684, the first insurance company in England was founded to provide fire insurance. Around the same time, Edward Lloyd’s coffee house in London – the precursor to Lloyd’s of London – emerged as a central meeting point for shipowners arranging coverage for their voyages. In the United States, the first insurance company, the “Friendly Society,” was established in 1735 in Charleston to write fire insurance. It failed only five years later, in 1740, after a major fire devastated large parts of the city.

Regulators began to worry about solvency, fair pricing and market conduct. They imposed rules on how insurers set rates, structure policy terms, invest their assets and finance their operations.

Regulation plays a critical role in the insurance industry:

Solvency: Regulators aim to ensure that insurers can meet their long-term liabilities and avoid market exits. Insurers must hold sufficient capital to cover future claims and obligations.

Rates and Forms: Insurance companies are regulated in how they set prices and structure policy terms. This ensures premiums are fair and contract terms are transparent. Standardized policies also allow consumers to compare offerings and ensure that promised coverage is delivered.

Market Conduct: Regulators oversee insurers’ business practices to ensure compliance with legal standards and protect consumers from unfair practices.

Permitted Investments: Insurers’ investment activities are regulated to prevent excessive risk-taking that could jeopardize their ability to meet claims.

Capital Structure: Regulators require insurers to maintain a balanced ratio of risk, premiums, and equity.

For standard mass-market products, this regulatory framework works well. But it also has side effects: it makes the admitted system slow to adapt to new risks and reluctant to take on complex or hard-to-model exposures.

The surplus lines market emerged as a response to these limitations. Initially, many of the non-standard risks were placed with foreign insurers, particularly at Lloyd’s of London – a marketplace of specialist underwriters that has been willing to insure unusual risks for centuries.

Over time, U.S. states introduced their own surplus lines laws, allowing certain unlicensed or non-admitted insurers to write specific types of business under defined conditions. New York was an early mover with laws on surplus lines insurance in the late nineteenth century. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), founded in 1871, later developed model rules and tax frameworks for this segment.

Risks that standard insurers decline are channeled into the E&S market. This segment is characterized by the absence of prior approval requirements for policy forms and rates. As a result, E&S insurers can design policies around the specific needs and risk profile of each policyholder, flexibly structuring contracts and setting prices to provide tailored solutions for unusual or complex risks.

This flexibility creates an open, adaptive market that particularly benefits policyholders whose needs cannot be met in their state’s regulated admitted market. Surplus lines insurance enables coverage on the basis of individual requirements and makes it possible to insure risks that would otherwise remain uninsured.

In summary, the E&S market functions as a safety valve within the broader insurance system. As a subsegment of the P&C market, it accommodates risks that standard carriers cannot or will not underwrite by allowing highly customizable policies and individually set premiums. Given sufficient pricing flexibility, almost any insurable risk can, in principle, be placed in the E&S market.

4. What lives in the E&S world?

4.1. Types of risks that migrate into E&S

Risks that end up in the E&S market are diverse, but they tend to fall into a few recurring categories.

The first group are new or rapidly changing risks. Economic and technological progress constantly creates new business models and new exposures. Cyber risk is an obvious example: as more commerce and data move online, companies need coverage for data breaches, business interruption due to cyber attacks and liability for privacy violations. For many years, admitted carriers were hesitant to offer broad cyber coverage; E&S insurers stepped in to fill that gap.

Structural changes in climate have increased the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, causing significant financial damage. Properties in areas with elevated catastrophe risk – for example along hurricane-exposed coasts or in wildfire-prone regions – are often written in the E&S market once admitted carriers restrict capacity or tighten terms.

Another group are very large or concentrated risks that exceed the capacity of standard markets. For example, large industrial plants, chemical facilities or energy projects can produce losses in the hundreds of millions of dollars if something goes wrong (e.g. if a toxic chemical is released). Admitted carriers may not be willing to take on that level of exposure under their usual rate and form constraints, especially if the risk is highly specialized. E&S carriers can assemble bespoke programmes for such clients, often involving multiple insurers and reinsurers sharing the exposure.

A third group are unusual classes of policyholders or activities. These can range from entertainment venues and music festivals to indoor trampoline parks, race tracks, cannabis-related businesses. Many of these classes appear on state “export lists” – lists of risks for which certain E&S placements are explicitly allowed or for which the usual requirement to try the admitted market first is relaxed. We will come back to the regulatory details of white lists, black lists and export lists in Part 2.

Finally, there are policyholders with challenging risk characteristics. These can be businesses with poor loss histories, startups with limited operating experience or companies in high-risk industries or locations. They may not be inherently uninsurable, but they do not fit the underwriting templates of standard carriers. For these policyholders, the surplus lines market can offer tailored solutions at prices that reflect their specific risk profile.

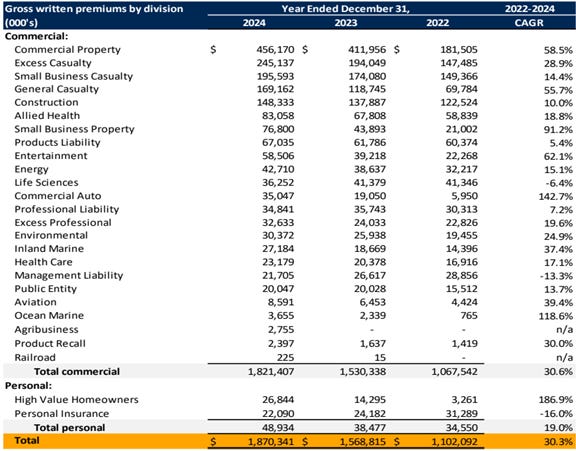

Kinsale’s own product set mirrors this variety. The company writes a wide range of property and casualty lines, including commercial property, general liability, excess casualty, construction, allied health, life sciences, entertainment, energy, environmental and various professional and management liability covers. The common thread is not a particular line of business but the fact that all of these policies are written on a surplus lines basis for risks that could not be placed in the admitted market on acceptable terms.

5. Who are the players in this ecosystem?

5.1. Policyholders and distribution channels

To understand Kinsale’s competitive advantage, it helps to map out the main actors in the (specialty) insurance ecosystem.

At one end are the insureds – the policyholders. They can be individuals, small and mid-sized businesses, large corporates or non-profit organizations. In the E&S context, what they have in common is that their risk does not fit neatly into the standard products offered by admitted carriers.

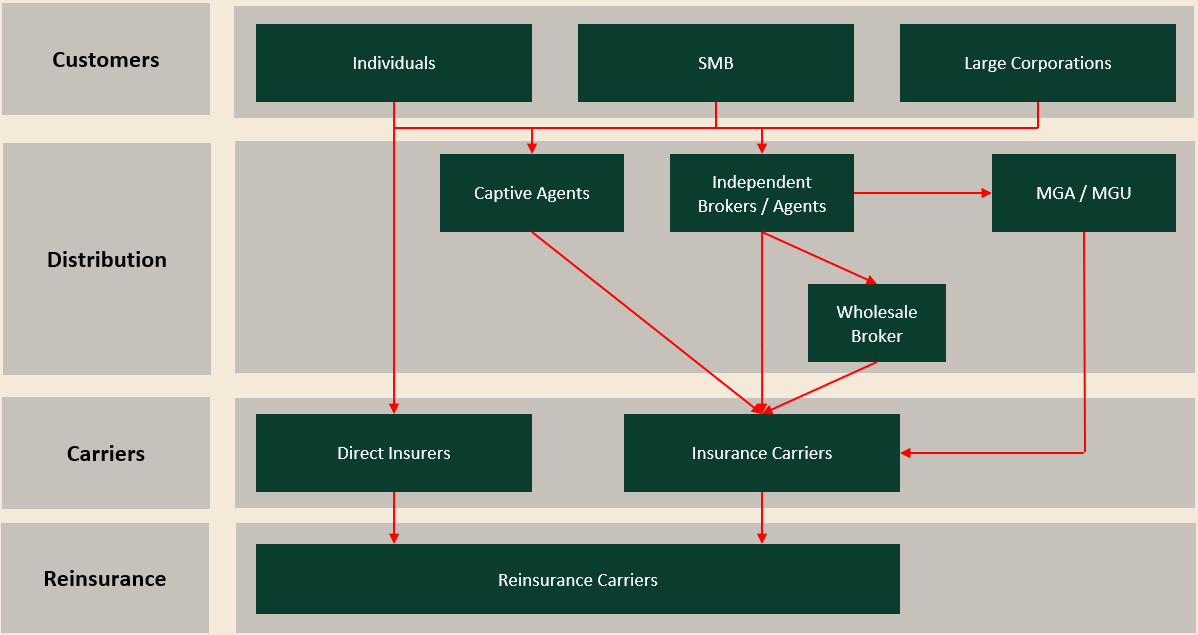

Between the policyholder and the insurer sits the distribution system which connects policyholders with insurance companies.

Captive agents work exclusively for a single insurance company and sell only that company’s products. They are either directly employed or contractually tied to the insurer, which means they do not offer competing products. This setup gives them deep familiarity with their own company’s offerings and access to extensive training and support, often backed by a strong brand. The trade-off is a limited product range: customers are restricted to one insurer’s solutions, which may not always be the most competitive option available in the wider market. Captive agents are typically compensated through commissions on the business they place.

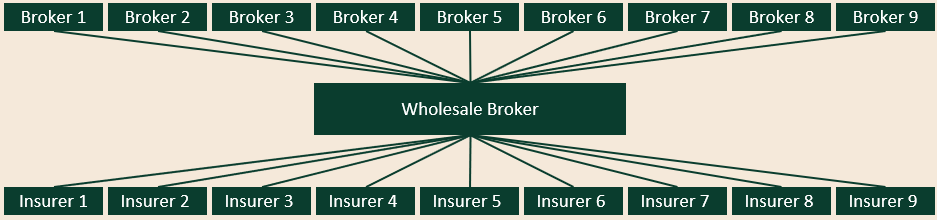

Wholesale brokers act as intermediaries between retail brokers and insurance companies and does not interact directly with end clients (i.e. policyholders), particularly for complex or non-standard risks that are placed in the E&S market.

Wholesale brokers give retail brokers access to specialized and hard-to-place insurance markets that would otherwise be out of reach, using their expertise and relationships with insurers to help structure and place coverage for complex risks.

The wholesale broker knows which specialty carriers or Lloyd’s syndicates might be interested in a given risk and how to structure the placement. Wholesale brokers are typically compensated by the insurers with whom they place business, usually via a commission that is a percentage of the premium. This means that from the insurer’s point of view, broker commissions are a central component of the expense ratio.

Managing General Agents (MGAs) and Managing General Underwriters (MGUs) are specialized intermediaries with delegated authority from insurers. They can underwrite, bind coverage and sometimes handle claims on behalf of one or more carriers. In effect, they are outsourced underwriting offices for specific niches or regions. This model can be powerful for reaching fragmented markets, but it also introduces another layer of economics and potential misalignment: MGAs are often paid based on premium volume, while the insurer bears the ultimate underwriting risk.

Unlike MGAs, MGUs typically do not handle broader administrative tasks or claims management. Instead, their work is concentrated on underwriting and risk evaluation processes. While MGAs oversee a broader range of functions—including underwriting and various administrative responsibilities—MGUs specialize more narrowly in underwriting and risk assessments.

In personal lines, captive agents – who sell only for a single carrier – and independent agents are the dominant channels. In commercial lines, and especially in E&S, independent brokers and managing general agents (MGAs) play a larger role.

Insurers differ in how they acquire customers. Direct insurers sell policies straight to end customers, often via online channels. They are typically admitted, standardized carriers focused on simpler B2C products. This model works well for straightforward insurance needs such as auto, home or basic life insurance, where products are relatively easy to compare and can be purchased without extensive customization or the involvement of intermediaries.

Reinsurance is, in simple terms, insurance for insurers. Primary insurers can transfer part of their risk to reinsurers, thereby reducing their own exposure as reinsurers assume a share of future claims. Reinsurers, in turn, can reinsure portions of their own portfolios through retrocession, spreading risk even further across multiple parties and strengthening the overall stability of the system.

Because primary insurers regularly cede parts of their business to reinsurers, they effectively act as distributors of risk on behalf of the reinsurance market. In return, they typically receive a commission but must also pass on a portion of the premiums to compensate the reinsurer for the risk taken. Reinsurance allows insurers to manage their risk profiles more effectively, stabilize earnings and increase their capacity to underwrite new policies.

We will dedicate a full part of this deep dive to reinsurance later.

Kinsale deliberately chose a different path. The company does not rely on MGAs for its core business. It works directly with wholesale brokers and keeps underwriting authority in-house. That means more control over risk selection and pricing, lower commissions (one of the main expenses for an insurer), a tighter feedback loop between underwriting and claims and a clearer line of sight on the economics of each account.

5.2. Types of E&S carriers and where Kinsale sits

On the carrier side, the rating agency A.M. Best divides the E&S market into the following main segments.

Domestic Professional Companies are U.S.-based insurers that write at least half of their total direct premiums on a non-admitted basis.

Domestic Specialty Companies are U.S.-based insurers that operate partly on a non-admitted basis, but whose direct surplus lines premiums account for less than half of their total direct premiums.

Regulated Alien Insurers and Lloyd’s syndicates are non-U.S. carriers that submit their financial statements, audit reports and other information to U.S. regulators in order to be recognized as eligible surplus lines markets.

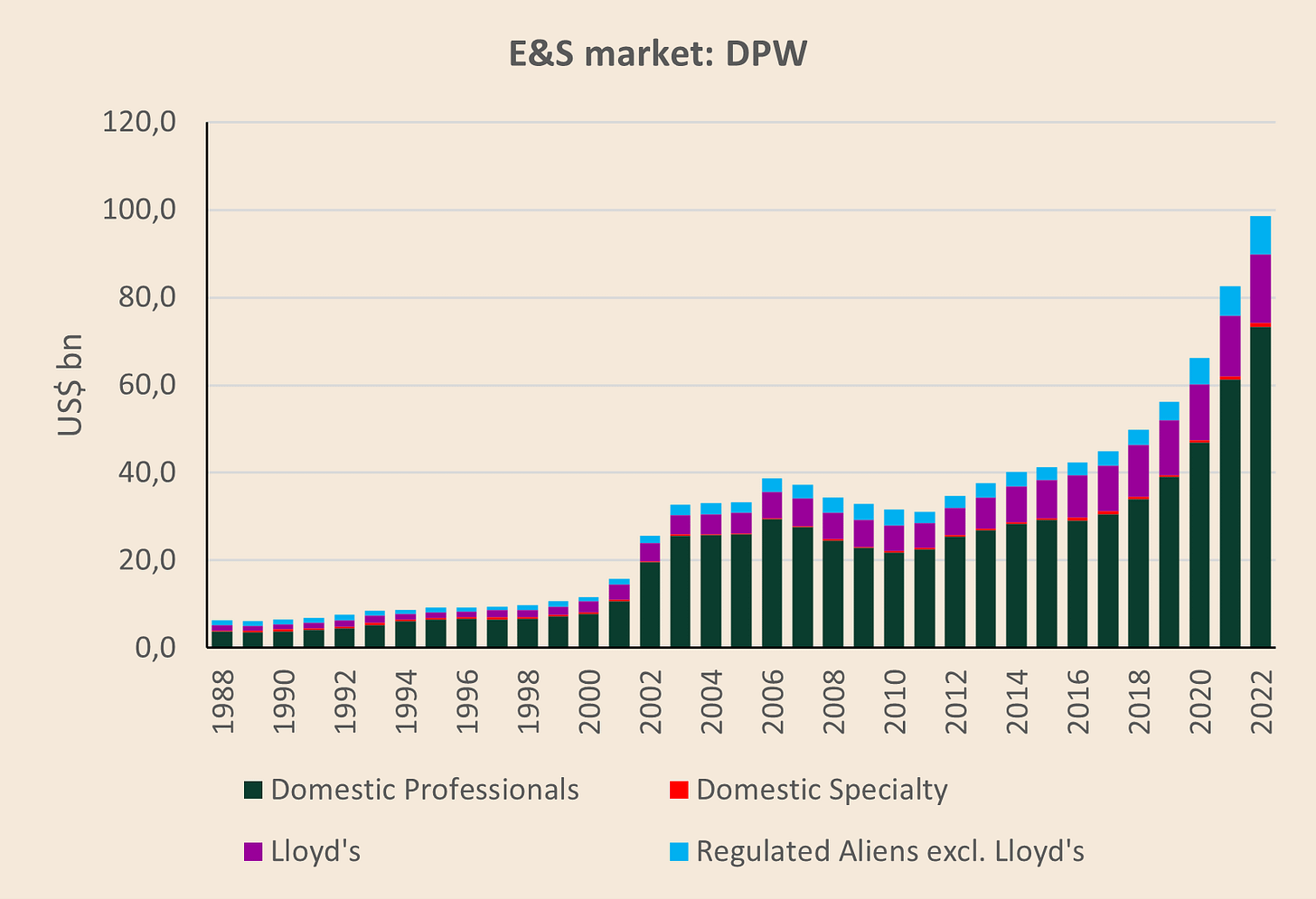

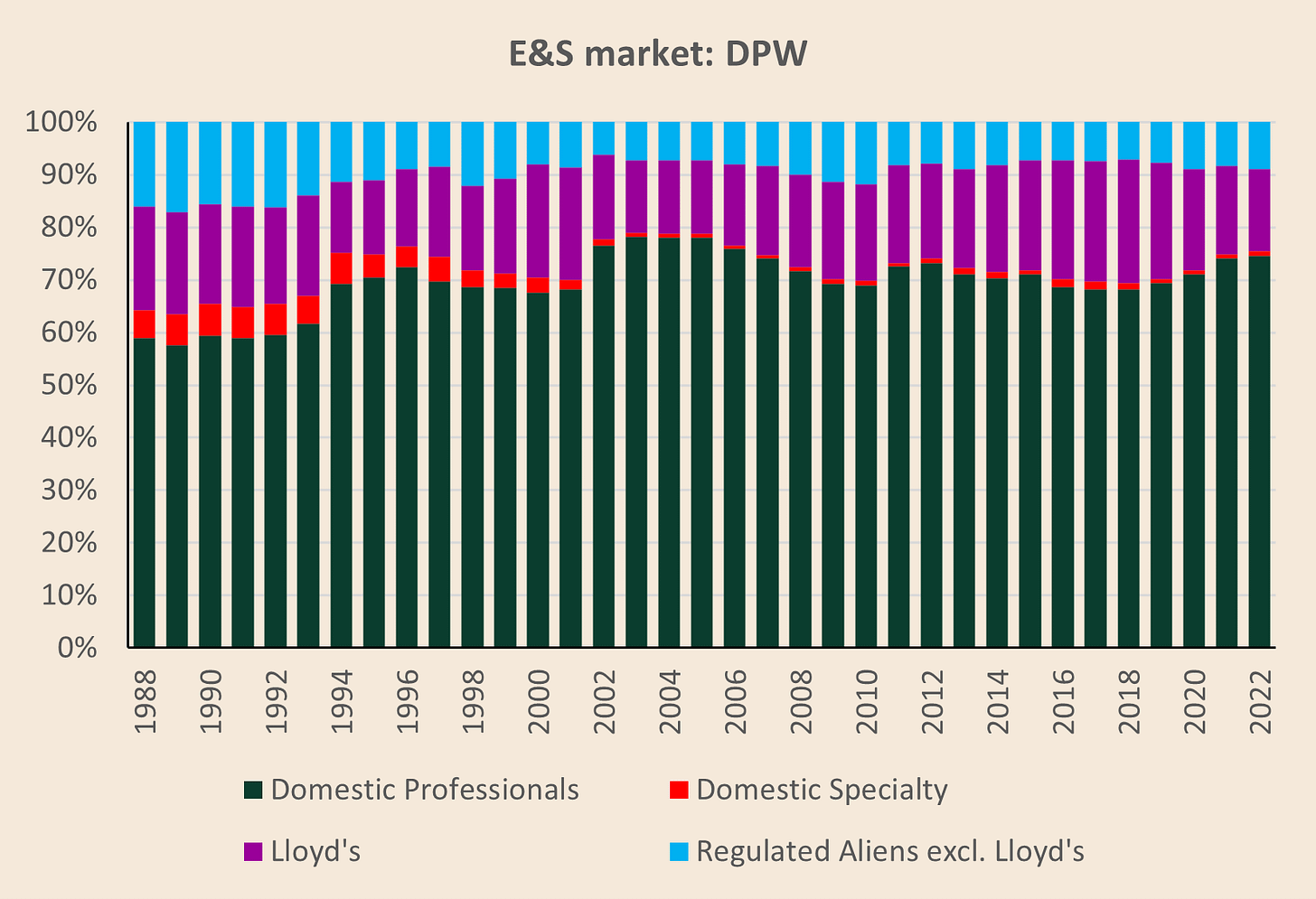

Historically, domestic professional and specialty companies together dominated the U.S. E&S market. Over time, their combined market share has eroded somewhat, while Lloyd’s and certain regulated alien insurers have maintained or modestly expanded their presence. The overall surplus lines market, however, has grown significantly since the late 1980s. Charts of direct premium written (DPW) by segment show that all four groups have increased their absolute premium volumes, even if their relative shares have shifted over time.

Within this landscape, Kinsale is best thought of as a domestic professional company focused entirely on surplus lines business. It is a U.S.-domiciled insurer that writes E&S policies across all 50 states and certain territories, uses a wholesale brokers as its main distribution partners and keeps underwriting and claims handling in-house. This clarity of focus simplifies the strategy and sharpens the incentives: Kinsale lives or dies by how well it underwrites and services E&S business in its chosen niche.

6. Setting up the next parts: time and tails

There is one more building block that we will need later when we analyse Kinsale’s loss development triangles, reserving behaviour and reinsurance programme: the difference between short-tail and long-tail business, and between occurrence and claims-made coverage. These concepts determine how quickly losses emerge, how long reserves stay on the balance sheet and how much judgment is involved in setting them.

The main difference between Short-tail and Long-tail insurance refers to the time span between the occurrence of a loss event and the final settlement of the claim.

Short-tail lines are those where losses are reported and settled relatively quickly after the insured event. Property insurance is the classic example. A building burns down, the insured reports the claim, an adjuster assesses the damage, and the insurer pays within months.

Long-tail lines, by contrast, can take several years to be reported and settled, as the damage might be discovered long after the actual loss event has occurred. For example, an employee may work with asbestos for many years without realizing they are being exposed to hazardous materials. Only much later do they file a personal injury claim related to this toxic exposure.

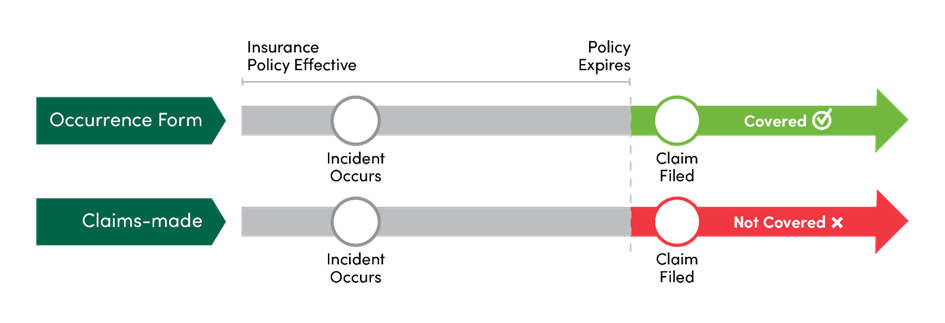

Occurrence policies respond if the loss event occurs during the policy period, regardless of when the claim is reported. The timing of when the claim is made does not matter as long as the event that led to the loss happened during the policy’s term.

Claims-made policies, in contrast, respond only if the claim is reported during the policy period (or within an agreed extended reporting period), regardless of when the underlying incident actually occurred. This means that the policyholder must have a valid policy in place at the time the claim is made for the damage to be covered, even if the event causing the loss occurred prior to the policy period.

Let’s make this clear with an example:

An architect designs an office building in Year 1; the building is completed and becomes operational in Year 2. In Year 4, the owners discover serious construction defects that are traced back to a design error made by the architect. They file a claim against the architect in Year 4 to recover the repair costs. During the construction phase, the architect had the following insurance arrangements:

a) Occurrence-based professional liability insurance

Under an occurrence policy, the claim is covered even though it is reported in Year 4. The decisive factor is that the damaging event – the design error – occurred during the policy period, i.e. while the occurrence policy was in force. The architect does not need to have an active occurrence policy in Year 4 for the claim to be covered, because the trigger for coverage is the time of the negligent act, not the time of the claim.

b) Claims-made professional liability insurance

Under a claims-made policy, the situation is reversed. Coverage is triggered when the claim is made, not when the underlying event took place. Since the claim is filed in Year 4 and there is no longer an active claims-made policy in force at that time, the insurance does not respond. Even though the design error occurred in Year 1, the lack of an active policy in Year 4 leaves the architect without cover for this claim.

A claims-made policy typically comes with lower initial premiums and allows relatively flexible adjustments of limits and scope over time. The trade-off is the risk of coverage gaps if the policy is not renewed. Claims-made cover is often attractive for professionals who initially seek cost-effective protection but must pay close attention to continuity of coverage.

An occurrence policy, by contrast, offers permanent protection for events that take place during the policy period, even if related claims are reported many years later. This structure is often easier to understand and provides greater certainty, because coverage is tied to the time of the act or omission rather than the time of the claim. However, occurrence policies are generally more expensive than claims-made policies, as they provide broader, long-term protection.

Long-tail occurrence business is particularly challenging for reserving, because the insurer may have to estimate ultimate losses many years into the future based on limited information. Long-tail claims-made business is still complex but somewhat more contained in time.

Insurers therefore analyze their books by accident year – the year in which the underlying loss event occurred – rather than purely by the calendar year in which claims are reported or paid. When we later look at Kinsale’s loss triangles and the question of how conservative its reserves are, this accident-year perspective will be central. For now, it is enough to keep in mind that short-tail business produces fast feedback and relatively low reserving uncertainty, while long-tail business involves more judgment, more time and more potential for surprises.

In Part 2, we’ll cover regulation and answer the question why E&S looks the way it does.

Thank you for sharing this illustrative piece; helpful reading and looking forward to Part 2.

This is a wonderful company!